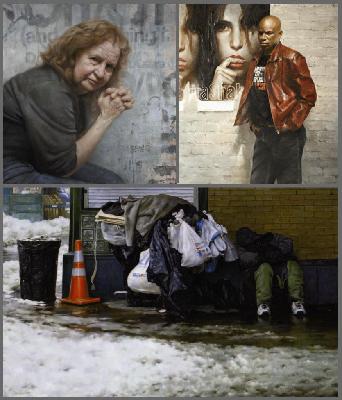

Is it uplifting enough to count as art if a painting stirs the soul to compassion?

Does that kind of upliftment via images of impoverished or disenfranchised people create beauty?

Does evoking the deeper sense of the degradation and pain of our shared humanity–‘there but for the grace of God go I’–catapult the viewer out of the stupor of our daily lives into a state where transcendence and transformation can occur?

These questions came to mind last night as my husband Sabin and I attended a panel discussion at the Salmagundi arts club. Our friends dancer Lori Belilove and musician John Link accompanied us; Lori had suggested the outing.

Sabin was quick to dismiss most of the paintings: “They are illustrative.” He meant that as “merely illustrative,” criticism indeed from an artist of Sabin Howard’s caliber. He was right: most of them are illustrative. This exhibit at Salmagundi is uneven, though ambitious in scope: “Ask artists to paint instant history, to reach into their souls and put onto canvas their expression of the toughest economic times since the great depression.”

Then there were Burt Silverman’s paintings, which were informed by intelligence and grace, so that even the ugliness of the subject matter did attain something, some higher metabolism of representation and humanity.

The panel discussion ranged from from curatorial matters and historical imperatives to practical ones: Who buys these paintings? There is always that scourge of investment hanging over the art market, the real or imaginary perception that a piece of art is a safe place to store value. Artist Max Ginsberg mentioned that taste is too often made by someone who is promoting something for sale, and that when people see an abstract piece that doesn’t move them, the trend is to say, “I don’t understand it” rather than “it doesn’t move me.”

From me, novelist Traci Slatton: Honest people, who aren’t afraid of pissing off the emperor by mentioning his nakedness, will say, “It’s ugly crap.”

Burt Silverman (yes, I am a huge fan of his work and his eloquence) was asked about the political nature of this exhibit. He said that he resists the categorization and politicization of art because those are temporal and transient labels. I agree that art should resist time. It was most fascinating to hear him come out and claim, “I am uncomfortable with the increasing dominance of photography and the corresponding abdication of the artist’s personal human vision.” He talked about the importance of the “fulcrum of discovery” in art.

These are matters of some importance. The exhibit, though uneven, is worth seeing. These are not modernist nor post-modernist pieces; they are not done with sneering irony, denigration of beauty and value, and adolescent mockery of the common humanity that twines us together. Are they the next step in the evolution of art? Sabin says “no,” that an integrated vision of the heroic ideal and oneness of life comprise the “next step.” But these are an important part of the transition, as the collective consciousness grows out of silly modernism.

The Salmagundi Club is located at Fifth Avenue and 12th street.