My husband the sculptor claims to know I’m happy when I ask him a deep, unanswerable question at bedtime. He’ll move around the bedroom and bathroom, methodically performing his evening ablutions, putting away his glasses, taking out from his armoire another pair of plaster-encrusted jeans (sculpting is construction work for geniuses). Just as he’s sliding into bed beside me, I’ll turn troubled eyes on him. “How does anyone ultimately know God?”

“Uh oh, you must be happy,” he says. He sinks down into the bed and closes his eyes. Usually that’s when I lean over and put my nose next to his. I’m the persistent sort, not easily distracted.

“But really, what’s the nature of sensory apparatus for the divine?” I’ll say. Or something of that nature, eliciting a groan and sometimes also a kiss. My husband is a calm, earthy man who works with his hands putting clay on an armature, with his head in considering morphology and psychology, and with his heart in his love for truth and beauty in the human body. He doesn’t spend a lot of time pondering the ineluctable.

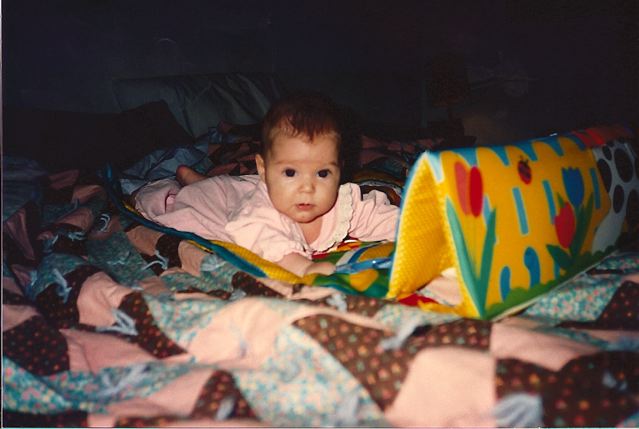

But novelists do. And lately I’ve been thinking about free will and fate, and their intertwinings in the individual life. The life I have been ruminating on is my daughter’s.

She was not accepted at her top college choice. She was waitlisted at her second choice, and she received two other waitlists at schools that were high up on her list. She was accepted at three great schools, and she’s weighing her options.

She has had many accomplishments on several fronts, and she had a bright outlook for her college options at the end of her junior year. That changed with her first semester senior year grades, which were not as stellar as they always have been in the past. Now, 3rd quarter senior year, her grades are back up. Clearly it was not a matter of ability. Something else was going on.

So what was going on? A temporary brain glitch, brought on by the intense stresses of the college process, about which so much was written this year? Trauma and shock at what she experienced and witnessed in an impoverished foreign city, when she went on a medical mission with a charity? Self-sabotage? Or did she simply not want to attend the family alma mater? Was she trying to separate herself out from the family DNA, and this is the only way she knew how: shoot herself in the foot so she had an out? I keep thinking of Nicolas Cage and Cher in Moonstruck, when she tells him that he was a wolf who chewed his own paw off to escape the trap of an ill-considered marriage. Isn’t it a shame he couldn’t get out without the suffering and pain of the loss of his hand?

It hurts to see her hurt. Some part of her deeply wanted to be accepted, and that part is now in pain. And she feels embarrassed in front of her peers, like they’ll think she’s stupid. And she hates the extended anxiety and uncertainty of the waitlists, though I’ve counseled her to do due diligence on her current options. “Write a gracious letter accepting the waitlists, and then tuck them away in the back of your mind,” I said. She nodded to me, her big eyes filled with sadness.

But it’s not about my counsel anymore. It’s about her own choices and actions, and the consequences of them. She’s getting ready to leave and begin the great journey of her own self-determined life. She’s taking up her own destiny, with its mixture of fate and free will, good luck and bad luck, synchronicity and accident. All I can do now is give her lots of love. And serve the same function as that corrugated strip of roadway beside highway lanes: make a bumpy, obnoxious noise when she strays too far out of her path. It’s one of the great unanswerable questions, in my mind: why it is that the parent-child relationship is only successful when the child leaves.