Check out my article on the HuffPo…

My article on the HuffPo

Dear Readers:

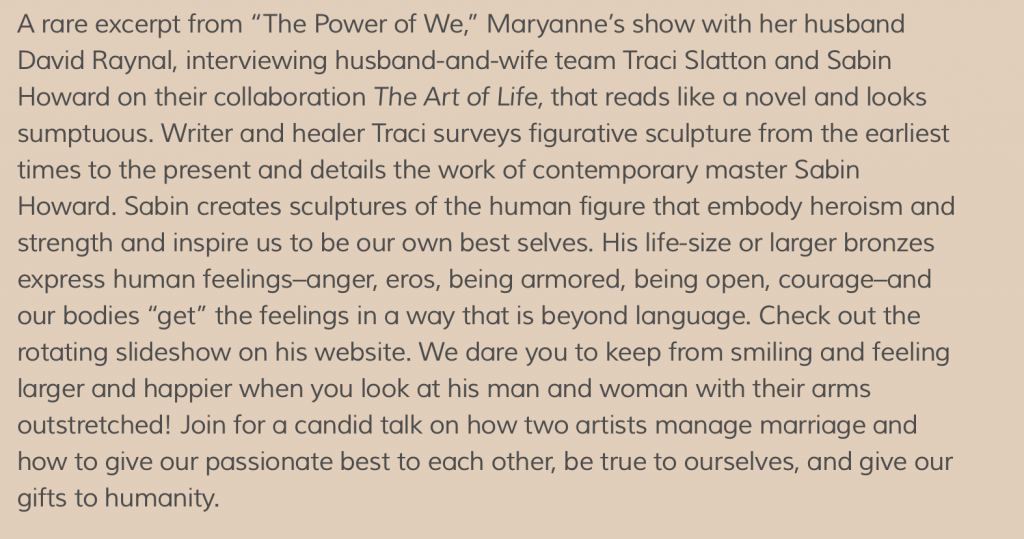

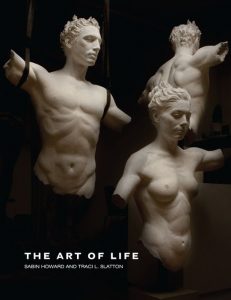

Take a peek at my article on How to Look at and Enjoy Sculpture on the Huffington Post.

***

Traci Slatton’s ‘How To Look At And Enjoy A Piece Of Sculpture In 6 Steps’

With everyone’s inbox topping 2500+ emails, and Netflix streaming a million movies a minute, we’re losing sight of the sensual pleasure of the concrete world. It’s not that eEverything in the iWorld isn’t fun and useful, just that there’s more to life. More to think about, more to experience in tangible ways, more that can enrich our lives. Especially more beauty and wonder.

Paintings are easy to enjoy because they operate by way of immediate visual impact. We have an instant impression of light, color, line, and shape. Are there halos, gold auras, and a crucifix? Gothic praedella. Is it a blurry pastel? A great Monet. Does it bulge and heave? Van Gogh, that tormented genius! Is the spirit rotting, in a masterful scene from the Bible? Caravaggio, the murderous master. Even early cave drawings arrest us: stick figures and aurochs outlined with archetypal simplicity, speaking to our most fundamental instincts and encounters in the natural world. We’re good with easily accessible two-dimensions, and we’re rapidly becoming virtuosos with no-dimensional, virtual representation. But what about a standing human form in three dimensions?

Sculpture, especially figurative sculpture, represents a dilemma for us 21st century dwellers.

We are three-dimensional creatures whose harried lives lead us to forget our own embodiment. Sometimes we barely remember to breathe, so enrapt are we in texting.

Sculpture is here to remind us. It’s three-dimensional, as we are, and it partakes of light and gravity, as we do. It is both subject and object of our witnessing. We have to slow down and be present with a piece of sculpture in order to get it. In this way, sculpture can point the way to pausing, grounding, and feeling.

Here are six tips for how to look at — and enjoy — a piece of sculpture:

1. What is the human form doing? Is it standing, seated, crouching? At a level that barely needs words because it’s ingrained into our primitive lizard brain, the pose of a body says something. A standing figure is active. A seated one is passive. This simple differentiation goes to the heart of the human condition: are we active or passive in our lives?

2. Are the arms outstretched? Are they pleading? Or do they reach out to dominate the world? Is the face upturned to catch the sun, turned aside in grief, arrowing downward in weariness? The pose and gesture give the rudiments of the universal story the sculpture is telling. The ancient Greek sculptor Lysippos put his Hercules in a standing pose, but leaning and dragged down, to say that it’s a monumental feat to stand and perform the labors.

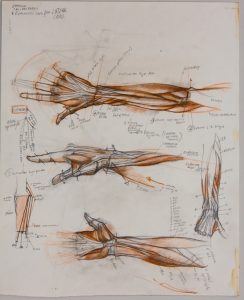

3. What is the body like? Is it young, mature, or old? Is it supple and curving, insinuating erotic tension? In the nineteenth century, classical sculptor Canova sculpted Pauline Bonaparte reclining on a couch, her lissome body reeking of grace and invitation. Or are the muscles thick and defined, meaty with their own power, bursting with life force energy? Look at Bernini’s Pluto for a mighty, mature man intent on possessing what he has captured in his hands. Morphology is biography, and that biography opens into the message of the piece.

4. There’s a more complex understanding of morphology. Most of us have the mistaken impression that realistic figurative sculpture is an exact copy of life. In fact, it’s highly abstracted, exhaustively designed. A sculptor looks at a life model and then creates a figure based on his or her own internal system of analysis. It’s extremely personal. If the sculptor is architectural in his system of representation, the emphasis will be on structure, on bones and muscles as geometric elements; the piece may be in motion, but there will be an underlying sense of organization, perhaps even of a grid.

If the sculptor is more narrative, more interested in the lively, dramatic aspect of sculpture, the piece will tend to move more, and to emphasize curves and surface fluidity. For example, think of Michelangelo’s heroic David, which has structured monumentality and gorgeously pluperfect anatomy. Now picture Giambologna’s Mercury (commonly known as the FTD symbol). Giambologna was a baroque sculptor whose fascination with curves led him to exaggerate them almost to the point of jokiness.

5. Pay attention to the medium, for it influences the design of the figure. Working with marble, the artist sculpts down to low points. With clay that is cast into bronze, the sculptor builds up to high points. This is a subtlety, but it informs the process all the way through to the finished piece. And whether bronze or marble, the piece will have a surface, a tactile element that evokes a feast of sensory impressions: soft lips, thick hair, smooth skin.

6. Most important, walk around the piece, seeing it from all angles, and ask yourself: Is it beautiful? What makes it beautiful? Is it pose, gesture, curves, structure, or even the spirit or energy of a piece? Look, feel, and trust your witnessing. It’s in that beauty that the viewer finds him- or herself, and is drawn back into primal, living essence. This is how sculpture is the antidote to modern life.

***

And if you haven’t yet voted for my dystopian romance FALLEN in the Paranormal Romance Guild Best of 2011 Reviewer’s Choice category, please send them an email mentioning FALLEN.

prg.contest@gmail.com

Thanks!

Traci