In the spiritual tradition in which I live and have my being, we say things like, “The choice is always between love and fear.” It’s a true summation, but it is also both clear and obscure, at the same time. That is, it’s the simultaneous horns of a dilemma that you face repeatedly if you are a person who shows up for her life.

Part of the problem lies in the meanings of the words ‘love’ and ‘fear.’ Fear is that tense, unsettled feeling that makes us want to fly off in the opposite direction as fast as possible. Or to fight and annihilate the other, or to freeze. But sometimes fear saves our life. It’s useful, necessary. The trick is to figure out when it’s appropriate and when it’s a regurgitation of a past memory, response, or feeling with only slender connections to the present moment NOW.

Which brings up the question of love. In our culture we see love as that sweeping hormonal experience of desire that unites two people in bliss, or as the sweet, fierce protective instinct a parent has for her or his children. Both are kinds of love, because love is that oceanic, ecstatic state of communion that encompasses all things. That’s the Kabbalistic version, as embodied by the sephirot Chesed, the kindness that goes beyond boundaries, the proactive expression of expansiveness that is a prime mover because it has no cause.

This definition feels intellectual and nebulous. Here in this material world, love needs be so much more concrete. At least in my opinion; I am a practical person. I find the Christian scriptures helpful in understanding love: “Love is patient and kind, love is not jealous; love does not brag and is not arrogant, does not act unbecomingly; it does not seek its own, is not provoked, does not take into account a wrong suffered, does not rejoice in unrighteousness, but rejoices with the truth; bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things.” (1 Corinthians 13)

This is a tall order, rather like the command given by Tom Hanks at the end of Saving Private Ryan: “Earn this.” It’s an impossible task and yet the necessary one, simultaneously. Here again we have both/and showing up, rather than either/or.

In my day to day life, love looks more like the Corinthian prescription than the Kabbalistic one, though I intend for Chesed to inform my actions at all times. I strive to be kind, humble, and truthful. Patience is not my strong point, but it is certainly my growing point. Most of all, for me, love looks like neither Testament, but like service. It is the small acts I perform as a matter of commitment, day in, day out, regardless of how I feel or what I really would rather be doing. Mostly what I would rather be doing is sipping wine in a cafe in Paris, or ambling through the Pinacoteca Vaticano while looking forward to a long, slow meal in Trastevere.

Instead, here in my little Manhattan kitchen, I cook broccoli and cauliflower for my children because cruciferous vegetables prevent cancer. I stock the refrigerator with non-rbgh milk and yogurt, and I look for snacks without obesity-causing, disease-predisposing high-fructose corn syrup. This is love. Pedestrian, certainly. Love, yes. And I will add that my children poke fun of me continuously for insisting on nutrition. I hope that the years of pushing fruits, vegetables, and whole grains will slowly accrete into good health for my children. But I’m not winning any accolades now, while they’d much rather be eating fritos and candy bars.

Along with the physical care-taking goes emotional care-taking. Sometimes that looks like me saying, “Great job! I’m so pleased that you worked hard and brought up that science grade!” Sometimes, because I am my children’s parent and not simply their good buddy, it consists of me saying, “A D in science is not acceptable. No TV or computer time until you do the work it takes to improve that grade.”

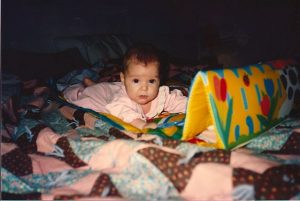

Children’s emotional needs change with time. Parents engage in a dance between toughness and allowing. My 17 year old daughter leaves for college in August; she is in the process of separating. This process requires her to beat up on me emotionally. I’m the punching bag. It doesn’t feel good but I guess it develops within her some necessary emotional muscle with which to stand on her own in the impending months.

Yesterday she was wait-listed at one of the colleges which she really liked. She was hurt and upset. Her immediate reaction was to blame me. I guess she experienced that painful fear that she wouldn’t have the life she longed for. So she yelled and screamed at me that nothing I had ever taught her was correct, and she had no faith in me, and nothing I said had any validity.

But I know I told her to keep her grades up at their customary stellar heights last semester, the first semester of her senior year, and she didn’t. She had a good excuse: she went on a mission with a charitable organization to a developing nation, and missing two weeks out of her senior year coursework left her struggling with an already enormous and ambitious work load for the rest of the term. Her experience with the charity was amazing, and what she saw in an impoverished city shocked her and woke her up in a way that staying home and getting all A’s wouldn’t have. But she paid a price for that awakening.

There was no point in explaining that she’d brought this on herself. That she’d made choices and was living with the consequences. She wasn’t strong enough to face the truth, in that moment. I hope she will be someday, because from what I’ve seen, the capacity for self-responsibility is the big dividing line between people who grow up and people who don’t, between good people and less good people. Yes, I make those distinctions: I am not a moral relativist. Some people are just not that great as human beings, despite all the juvenile “everyone’s okay” rhetoric that saturates our culture.

But in that moment with my daughter, who is brilliant, talented and hard-working, despite an uncharacteristic glitch last semester, and who deserves to go to any school she chooses, I didn’t bring up moral relativism. I just told her that I loved her, I wanted the best for her, and I had faith in her. She yelled some more. I just nodded. That, too, was love.

Much in this philosophy of love as commitment and service is not gratifying. It’s not glamorous and does not reflect an exalted self back to me. Much of the time it feels like a daily grind. Where is the exaltation, the ecstasy? I wonder that frequently.

A few hours later, my daughter called and apologized. That was love on her part, and I was proud of her that she could let go of her fear and come back into communion with me. “Most of all, mom, I don’t want you to be more upset than me over the college process,” she said. I told her I would try not to be. She still felt her fear. She also felt her connection with me, at the same time. I ache for her that she must face the waitlist. I ache for her that she will face rejection, cruelty, betrayal, and anguish all through her life. Life doesn’t turn out, for any of us, exactly as we want it to.

But I see in my beautiful daughter the woman who will choose love over fear, even while feeling them both at the same time. I see a young woman who takes two weeks out of her senior year to serve people she has never met: her form of Chesed-inspired love in action. The college she chooses will be lucky to have her. She’s showing up for her life, in all its contradictory, simultaneous pain-and-bliss glory.