The Physical vs. The Facebook

reprinted from The Indicator, volume XXVIII, issue 2, October 8, 2009

Exploring the effects of technology on our social lives.

I bring my phone with me everywhere. It sits in my backpack during class, next to my tray at Val and on that communal bench at the gym. It’s in my jacket pocket when I walk to town, and it’s charging on my desk at night. It’s in my purse at parties, or when I’m out seeing a movie, and when it isn’t in one of these places, it’s in my hand. My laptop, if not as frequent a companion, still manages to accompany me to most classes, to the library and even to Schwemm’s. Cut to Friday night. A few friends and I are scattered around the common room of my suite in Stone, casually watching TV and chatting. I’m sitting on the couch with my laptop on my knees, browsing Facebook. A friend of mine is checking her Blackberry. Another friend is playing an online game on his phone. I look around. Most people are either texting, IMing or playing with a phone or computer, while continuing to have a conversation and watch TV. We call this “hanging out.” Everyone is talking to each other, but no one is even looking at each other. We are all too busy distracting ourselves with various forms of digital technology.

This kind of activity is far from uncommon, especially in our age group. Generation Y grew up in an era of constant innovation in the area of electronics, and studies show that we use digital technology and the Internet with significantly more comfort and frequency than did members of earlier generations. From phones to computers to MP3 players, almost every college student is toting around a token of our electronic age. One question that inevitably rises from this nearly ubiquitous phenomenon is what sort of effect does it have on our social lives? In favor of exploring this, I’m going to disregard the academic merits of technology in order to delve into the inner workings of our culture’s most prevalent digital commodities, Internet sites and electronics companies, including a few possible reasons behind their widespread popularity. From this I hope to draw out an inquiry about the positive and negative effects that technology has had and continues to have on our social lives as young adults.

Looking at these issues, an appropriate place to start seems to be with the Blackberry. Over the past few years, Blackberry has grown into a common perpetrator of the coolphone-I-can-never-put-down frenzy. It began as the must-have handheld organizational tool among urban businessmen, quickly earning itself the nickname “Crack-berry” due to its owners’ penchants for incessant usage. But it soon spread into the realms of non-business and even teenage life. These days, as my 14-year-old sister desperately tried to explain to my mother over dinner one evening, “All the coolest girls in school have one!” Somehow, Blackberry made the transition from business tool to coveted socialite necessity, and Amherst can boast of at least as many Blackberry users as can any other elite liberal arts college campus in the nation.

On the other side of the marketing war, Apple and iPhone enthusiasts prove even more feverishly obsessed than their Crack-berry counterparts. Upon the release date of every slightly modified iPhone number-letter-letter, masses of consumers around the world pour into stores at 7 a.m. like churchgoers flocking to holiday services, ready to drop $300 or more to get their hands on the latest heavily marketed upgrade from Apple. As the self-deprecating owner of an iPhone, I have to admit to all of you-with shame-that I can totally dig it. Apple. You’re not even supposed to capitalize it.

Even now something about it looks wrong, like it’s lost some of its cool, its accessibility. It’s not even just that Steve Jobs meticulously crafted every detail of that company, from product design to customer support, to make it as universally appealing as possible. Or perhaps it’s just that. Without Jobs’ creative and organizational genius, Apple wouldn’t be the poster boy for friendly-yet-competent modernism that it is today. Cultish followers aside, people widely consider Macs to be the most “trustworthy” and “user-friendly” computers out there. Some even think that the iPhone is the biggest step forward in digital technology since the computer itself. It’s hardly surprising that Apple has made its presence felt on college campuses like our own. Between iPods and MacBooks alone you can hardly go an hour at Amherst without spying that gracious Apple logo somewhere-far beyond academic settings-with its preoccupied owner typing away.

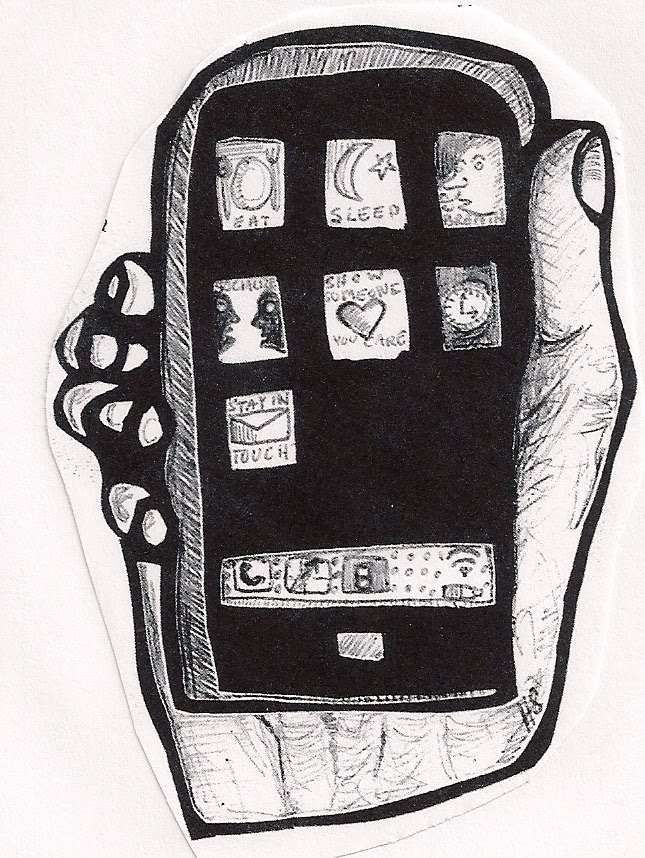

And yet, whether you own a Mac or a PC, an iPhone or a Blackberry, or even a mobile phone less worthy of worshipping, the underlying question remains the same: why are we all continuously using, coveting and even obsessing over digital technology? The answer seems to be that the motivations behind this cultural fascination are primarily social in nature. Whether it’s via texting, IMing, online gaming or Facebooking, most facets of digital technology provide some means for an individual to plug into a social network that is different from the one he or she is physically in.

Recognizing this phenomenon, it becomes easier to detect the seductiveness of the Blackberry. Aside from being almost as multifaceted as the iPhone, it has one other “improvement” that all other cellular phones lack: Blackberry Messaging. Blackberry Messaging, or BBM, is a messaging system that only works among Blackberry users (you need to provide your contacts’ PIN numbers). Unlike regular text messaging, you can scroll through the entire message thread as if it were an IM, so it’s more similar to a sustained conversation than separate texts. More importantly, BBM lets you see when your contact has read your message and when he or she is typing a response. It holds all the allure of bourgeois exclusivity while also providing even more intimacy (and even less options for escape) than texting or Instant Messaging. None of your BBM contacts have the option of ignoring you and getting away with it. It isn’t hard to see how readily these novelties play into both the friendliest and the cattiest aspects of our social lives.

And yet not even the ex-girlfriend infuriating capacities of BBM can compare to the innovations of one of the most popular Internet sites ever created: Facebook. Facebook along with MySpace (although the latter has declined somewhat in popularity since Facebook gained prominence) are the most widely used vehicles within our age group, in particular for the type of activity we call “social networking.” On a psychological level, these sites hold an undeniable appeal. Aside from the patent enticement of being able to essentially stalk any friend (or enemy) of your choosing without fear of being discovered, you also receive a web page entirely devoted to the online reinvention of yourself, complete with interest lists and hundreds of pictures for anyone you allow to see (which for many people is a thousand or more of their peers). The imaged representation of one’s self along with the secured anonymity of its viewers gives the ordinary individual an opportunity to become a sort of pocket-celebrity. Everyone gets to showcase himself, and everyone gets to judge other people’s showcases. This development has essentially redefined what it means to be a young person living in our society. With Facebook available for 24-hour use, more and more of us find ourselves checking it multiple times a day, and spending a considerable amount of time overall on the addictive website.

So what do we lose by continuously tuning into these nonphysical social networks? For one thing, we lose the ability to enjoy a night out without someone stopping the festivities for five minutes of contrived photo taking. For God’s sake Jim, I’m a doctor, not a professional model. Much more importantly, we lose a considerable amount of privacy. Facebook has given us a way to live our lives on a stage, and with everyone from our best friends to our most arbitrary acquaintances watching, can we truly say that our lives are still our own private matter? Privacy can be defined as “freedom from the observation, intrusion or attention of others.” Our generational compulsion to showcase ourselves on the Internet seems mutually exclusive with that concept. This applies to cellphone use as well. Can we say that we have privacy when we can’t even ignore a BBM at any hour without the person knowing? Can we ever say that we’re safe from the “intrusion or attention of others,” when we can be called or texted at virtually any time? It’s becoming necessary to reassess what the concept of privacy even means within the context of a digitalized lifestyle.

Linked to that idea is the notion of independency. A part of any healthy social life is the ability to be comfortable apart from it, to be independent. In this day and age, can a college student call himself an independent individual, or is he, along with all of us, already dependent on electronics? How much do we count on the digital diversions from physical reality that are always immediately available? In the words of the lategreat George Carlin, perhaps we all need to “turn off the Internet, the CD-ROMs and the computer games and .. stare at a tree for a couple of hours.” Why? Just so we can remember what it’s like to be alone. I doubt many of us students can say that we often spend the day truly alone, sans cellphone and all.

These are ideas that we, as the generation of digital technology-users, need to bring into the collective consciousness. However, I said that I would look at technology’s merits, so I’ll take the time to mention that we would be largely out of contact with many of our friends in distant places without the invention of cellphones, computers and the Internet. The course of our Westernized lives involves at least a few changing of schools and institutions in which we take part. Innovations like texting and Facebook have made it vastly easier for us to keep in contact with our friends from our younger lives when we move on to different colleges, universities or even different countries. We can remain in touch with almost anyone we have met. I myself still maintain an email correspondence with a girl my age whose family hosted me when I stayed in France a few summers ago. Given the relative labor-intensiveness of snail mail, I don’t know if we would have still kept in contact with each other if email hadn’t been invented. The ease of reaching out to faraway friends, family and acquaintances is a great thing, and by no means do I aim to devalue such benefits in this article. I’m sure the Amherst students who hail from different parts of the world can attest to that.

I do however hope that we can all weigh the benefits of nonphysical interpersonal contact with the cheapening of other important aspects of life. Ask yourself: How much do I really care about my privacy? My independence? How much do I even care about living in the moment? There’s a happy balance somewhere between these concerns, but we have to remember that the trade-off for close contact across distances is that we’re less connected to the friends right in front of us, and maybe even to ourselves.

Jessica Hendel ’12 is a Contributing Writer for The Indicator, a fortnightly journal of social and political thought at Amherst College.