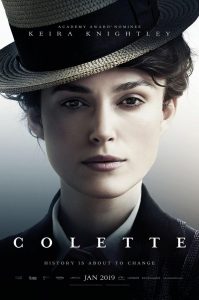

Colette, A Review

On a recent Saturday, my husband and I enjoyed date night at the Paris Theater. We watched the film Colette.

I’m a novelist and so the film held a special resonance for me. It’s always intriguing for me to see how other women do it–how other women wrestle with the great fanged beast of their need to write–how other women embrace the struggle of creativity and storytelling alongside the demands of partnership and self-actualization.

For me, there is no self without writing. If I’m not writing, it’s because I’m in a no-self space. That’s not a wholesome place for me.

Colette is turned on to writing by her husband Willy, who calls himself, in the film, a “writing entrepreneur.” He cheats on her and tells her to pen her thoughts and then proclaims her work to be worthless. Then he re-reads it and loves it. He pores over her prose with her and teaches her to edit and revise. At least in the film, he is instrumental to her discovering her talent.

Willy publishes her book under his own name. When it becomes successful beyond his wildest dreams, he locks her in a room to write another book.

Colette slowly wakes up to her own worth. Her self-awareness grows as she uncovers her individual sexuality. Her husband cheats but she begins to sleep with women–which he permits, as long as she doesn’t sleep with other men.

It’s comical when the husband beds her paramour and they both carry on with the libidinous lady in question.

There’s a kind of leftist-liberal-proselytizing fabric to this movie; the husband is an exploitative patriarchal scumbag and noble, victimized Colette naturally finds a supportive woman partner/lover. So many films these days are taken over by the need to preach leftist liberal values. I wish more films would focus on good storytelling and leave preaching propaganda to the politicians. It’s boring.

When a story delves deeply into the human condition, the spectrum of left-right, liberal-conservative falls away. What is left is meaning. That meaning is far more moving, far more convincing, than even the best propaganda.

In this case, the film transcends the current Hollywood piety. After all, Colette was a French novelist. She’s an archetypal French woman novelist. She actually lived the life and she did so before it was appropriated by a certain tiresome sector of post-modernist feminists–as if being a traveling mime with a woman lover is the only way to be a woman novelist.

I admire Colette but her choices wouldn’t work for me. I would never have been happy or fulfilled without children and a husband. Being a mother and wife contributes to, and enhances, my fruitfulness.

As painful as my situation is with one of my beloved daughters and with a dearly loved husband who took off for the antipodes, putting his own art before the family who needs him–despite everything–I was always supposed to be a wife and mother. And a novelist. And lately a screenwriter.

Willy exceeds his role, too, I think. Yes, he’s selfish, self-indulgent, egotistical, and riddled with vices. He’s also the fulcrum on which Colette’s own writing turns. He’s a catalyst for her. I find that real life is like this, that people are like this: marbled through with light and dark. Variegated. Bittersweet.

People are complex. They enter our lives bearing gifts, some laced with poison, some with nectar. Often the most difficult characters in our stories are our best teachers.

And beyond the propaganda is the story of a woman coming to own her own voice.

This is the essential struggle for a woman novelist: owning her own voice. Even for women who come across as strong, as I seem to, there’s vulnerability at the root. How do we embrace, own, and integrate that vulnerability with our creative talent?