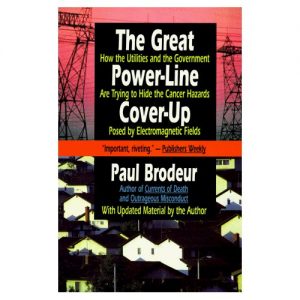

This article ran in our most recent bulletin as a contribution from a member, Paul Brodeur, a staff writer at The New Yorker for nearly 40 years.

In 1992, at the recommendation of Philip Hamburger, a colleague at The New Yorker, I donated papers relating to my 38-year career as a staff writer at the magazine to The New York Public Library. Among the papers were those connected to my investigations of the asbestos health hazard and its cover-up by the asbestos industry; the health risks posed by flesh-eating enzymes that had been introduced into household detergents; the depletion of the earth’s ozone layer by man-made chemicals; the dangers of exposure to microwave radiation; the ills caused by exposure to electromagnetic fields emitted by power lines, and the land claims of the Native People of New England. The Charles J. Liebman Curator of Manuscripts when I made my donation was Ms. Mimi Bowling. Five years later, Ms. Bowling conducted my wife and me on a tour of the Library’s Bryant Park Stack Extension, a vast underground vault beneath the park containing 42 miles of movable shelving units, where she showed us my papers, which had been processed and stored. She told us at the time that the documents we viewed constituted the permanent collection of my papers.

Following that tour, I donated a small amount of additional material to the Library, but was never contacted by anyone there until I received a letter from William Stingone, the present Charles J. Liebman Curator of Manuscripts, on April 23, 2010-18 years after my original donation. In his letter, Stingone informed me that, “As you know, we did a preliminary inventory of your papers soon after they first arrived at NYPL in 1992,” and “I am happy to report that we’ve now completed the final processing of those papers and your subsequent donations.” In the course of final processing, he said, “we identified a substantial amount of material that we chose not to incorporate into the collection.” He offered to send it to me within a month or, if I chose, he would “dispose of the material here.” “Over the past several years,” he explained, “we have had to become even more discerning as to what we retain. As I’m sure you understand, we need to manage our ever-diminishing resources, including space, even as our collection grows.”

Shortly after receiving Stingone’s letter, I contacted Ms. Bowling, who had left the Library in 2001, after 13 years as Curator of Manuscripts. (She is now a consult ing curator in private practice, as well as a member of the faculty at Long Island University’s Palmer School of Library and Information Science.) In an e-mail sent April 29, 2010, I told her that I had been surprised by Stingone’s assertion that only a preliminary inventory of my papers had been undertaken during her tenure as curator, and that their permanence was in fact pro visional. “I was never given any reason by you or your successors to know or understand either of those as sertions,” I wrote, and went on to remind her that, “when you showed me the display of my papers in or about 1998, you indicated and I had every reason to be lieve that the display constituted the final collection of my papers.”

On May 31, Ms. Bowling sent me an e-mail saying that she was “at something of a loss for words…. As far as I am concerned, it did not, in fact, take eighteen years to arrange and describe your papers and make them accessible for research. At least those of your pa pers that were accessioned in 1992 were judged by me and my superiors to be worth retaining and were, in my estimation, satisfactorily processed and shelved in the Bryant Park Stack Extension, where you saw them.”

Later in her e-mail, Ms. Bowling informed me that she had met Stingone for lunch several weeks previ ously, had told him of my shock at the deletions he had made in my collection, and had been assured by him that he would respond to me directly. (He never did.) She also said he “confirmed that your previously processed papers had been reviewed and a substantial quantity of materials removed.”

“Here is where I pretty much run out of words,” Ms. Bowling declared, “except to say that I am dis mayed. I had and continue to have the greatest admi ration for your work as an investigative journalist, and the senior Library staff who participated in acquisition decisions (none of whom, unfortunately, are still at the Library) concurred.”

Sometime in early June, I received a call from a woman named Victoria Steele, Director of Collections Strategy at the Library, who said she wished to discuss what had happened to my collection. Because I was in the middle of a meeting that could not be interrupted, I excused myself for not being able to talk with her. On June 12, I informed Ms. Bowling by e-mail of Steele’s telephone call and received a reply on the same day in which she declared once again that, “I valued your pa pers and considered them fully processed during my tenure…. Having expressed my shock and dismay to him [Stingone] and to you, I must now leave it to you and the NYPL to sort out this unhappy mess, but please do keep me posted from time to time.”

On June 20, I wrote a letter to Ms. Steele in which I said I assumed that Stingone “has informed you of Ms. Bowling’s shock and dismay over the continued culling of my papers many years after she showed me what she described as the final collection in the Bryant Park Stack Extension in the late 1990s.” I told her that “I no longer have confidence in The New York Public Library’s stewardship of the papers I donated more than 18 years ago,” and requested that she “return all my papers to me.”

On June 25, Ms. Steele telephoned me again to say she was sorry that there had been a “misunderstand ing.” At this point, I told her that the importance of the issues raised by Stingone in his letter to me of April 23 and in my letter to her of June 20 could not be ade quately addressed over the phone, and required the professional etiquette of a written response. In a letter to Ms. Steele on June 28, I reiterated this position and asked that she respond to my previous request for the return of my donation.

A day later, I decided that there seemed to be little use in dealing with junior officials at The New York Public Library. On June 29, I wrote to Paul LeClerc, President and Chief Executive Officer of the Library, describing what had occurred to the collection of pa pers I had donated and enclosing copies of relevant documents-among them Stingone’s letter to me of April 23, Bowling’s e-mails to me of May 31 and June 12, and my letters to Steele of June 20 and 28. In the fi nal paragraph of my letter to LeClerc, I said that I hoped the return of my donation could be arranged “at our mutual convenience,” and that he would read the enclosed letters and e-mails, “for they provide in sight into the workings of the Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division that may well concern scholars and authors who are considering donating their pa pers to the Library.”

I sent my letter and enclosures to LeClerc from my local post office on Cape Cod by overnight mail and was surprised to receive an e-mail from him the next afternoon. “I can certainly understand your reaction to having it suggested that a very substantial portion of your archives, which you gave to the Library in the early 1990s, be returned to you,” he wrote. “And I apologize for the distress that this has undoubtedly caused you to suffer.

“If you would consider having a conversation between the two of us,” he added, “-at your conven ience and on Cape Cod if you like-before any deci sion is made about the archive, that is something I would very much appreciate. I’ve admired your work for years and hope that you will accept to meet with me to talk through this further.”

That same day, I sent an e-mail to LeClerc thanking him for his invitation and telling him I would be pleased to meet with him either on Cape Cod if he was planning to visit during the summer or when I next came down to New York City. He replied that he was not planning to visit the Cape but would make a spe cial trip if I so desired. During the next few days, I considered LeClerc’s offer in two lights. On the one hand, I had no doubt of its sincerity. On the other hand, it seemed strange to me that high officials-in this case, LeClerc and Steele-of an institution es teemed throughout the world as a repository for the written word should be so loathe to use it, and would seek to resolve the issue at hand through talk and con versation instead. For this reason, I decided to pursue the matter the way it had begun-in the epistolary form.

On July 4, I again wrote LeClerc, telling him that when I retired from The New Yorker in 1996 it gave me pleasure to look down upon Bryant Park from my of fice on 42nd Street and know that the papers relating to my 38-year career at the magazine resided in the Stack Extension below ground. I wrote that he was “right to assume that the Draconian deletions made from my donation to the Library … have caused me distress,” and went on to say, “It would appear that the Library has instituted a policy allowing continued reprocessing of a donor’s papers according to the dic tates of a succeeding curator, who is free to depart from the precedent set by a predecessor (in my case Curator Mimi Bowling) and to do so in drastic fashion and without any notice given to the donor either be fore his or her gift is bestowed or the deletions made.”

I also reminded LeClerc that Bowling and her su periors had judged my papers to be worth retaining and to have been satisfactorily processed and shelved in the Bryant Park Stack Extension at the time I saw them in 1997. I proposed that my collection be restored to the state Bowling described, and that my attorney and a representative of the Library draw up a letter of agreement defining the conditions under which it would remain in the Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division. In closing, I said I hoped he would agree that this proposal might “constitute an equitable solution to the problem that has arisen.”

When a month had passed without reply, I wrote LeClerc another letter, telling him that I was disap pointed not to have heard from him, and that it had become difficult for me to have confidence in the Library’s stewardship of my papers. With regard to the Library’s policy allowing continued reprocessing of a donor’s papers by succeeding curators, I wrote, “I truly doubt that any present or prospective donor would regard such a policy as being in his or her best interest.” I concluded the letter by requesting that if his response to the proposal in my letter of July 4 was negative, he have one of his representatives contact me about the return of my entire collection.

As it happened, LeClerc had written in reply to my letter of July 4 on August 4, the same day I wrote and sent my final letter to him. His letter had all the ear marks of having been dictated by the Library’s legal staff, which probably accounted for the month-long delay. LeClerc apologized “for any miscommunica tions that may have been made by current or former staff of the Library.” The second paragraph was sur prising, to say the least, because it impugned Mimi Bowling’s grasp of how the Library’s Manuscript and Archives Division functioned, her professional good sense, and, in light of her e-mails to me of May 31 and June 12, her probity. “When Ms. Bowling showed you the collection at the Library, it appears that she did not make it clear that it had not yet been processed,” LeClerc wrote. “That seems, unfortunately, to have contributed to the impression that the collection had gone through our archival processing procedures and that it would be retained in its entirety.”

Before Ms. Bowling became Charles J. Liebman Curator of Manuscripts at the New York Public Library, she served for 10 years as the Reference Librarian for Manuscripts at Columbia University, fol lowed by five years as Archivist and Supervisory Museum Curator at the Edison National Historic Site, which is part of the Department of Interior’s National Park Service. After her 13-year tenure at the NYPL, she became Director of Archives at Random House. To suggest that a curator and archivist of her experience did not know what she was doing in her job, and to try to make her a scapegoat for a situation that the President and Chief Executive Officer of the Library seemed anxious to resolve by offering to travel from New York City to Cape Cod in order “to talk through this further,” seems deliberately disingenuous.

Whatever the case, the input of the Library’s legal staff became additionally apparent in the fifth para graph of LeClerc’s letter: “The Deed of Gift you signed on March 21, 1993 (copy enclosed) is clear and unam biguous in the Library’s view and is not subject to renegotiation.” (Paragraph 6. of the Deed of Gift de clared that, “The Library reserves the right to return to Donor any item that it does not choose to retain in the Papers,” and that “If Donor (or, if Donor is deceased, Donor’s estate) declines to accept such items, the Library may dispose of the same as the Library deter mines in its sole discretion.”)

LeClerc offered to hold the material the Library had decided not to retain for my review, but for no longer than a year from the date of the letter. He also suggested that if my attorney wished to discuss the matter, he should contact the Library’s Deputy General Counsel. Having handed me my head on a legally en graved platter, and indicated that the Library would play dog-in-the-manger with my papers, he concluded by assuring me that “I look forward to meeting you in person, not only to explain in greater detail the Library’s policies and procedures but also to have a chance to converse with a journalist whose work I greatly admire.”

In retrospect, it seems clear that I should not have donated my papers to an institution whose lust for ac quisition places previous gifts at risk of drastic dele tion, and whose highest official apparently thinks nothing of making the Orwellian claim that the Li brary’s former Curator of Manuscripts did not make it clear that my collection of papers had not yet been processed when she showed it to me 13 years ago, even though he had been sent two e-mails written by her a few weeks earlier-the first stating that she considered my papers to have been “satisfactorily processed and shelved in the Bryant Park Stack Extension, where you saw them,” the second declaring that she considered them to have been “fully processed during my tenure.”

In September, I wrote Ms. Bowling to bring her up to date on what had transpired between the Library and me during the summer. She replied in a letter dated September 29, in which she said that she wished to comment on the portion of LeClerc’s letter of August 4, “implying that I knew but did not tell you that the collection that I showed you in 1997 was not processed. That, as you and I both know, is simply not true: the collection was, in fact, processed.”

At this point, I have come to the conclusion that I should have given my papers to an environmental organization, a school of journalism, or a small univer sity-any of which might have been more appreciative of them than The New York Public Library. However, that is water over the dam. The fact is that anyone signing the Deed of Gift to The New York Public Library (or a similar deed of gift to any institution) should consider the possibility that future curators may undo assurances made at the time of donation by their predecessors. Rather than place one’s trust in such institutional assurances, donors would be well advised to dictate the terms of a donation agreement with the assistance of an attorney, in order to protect the integrity of the donation in the years to come. Otherwise, five, ten, 18 (as in my case) or 30 years down the road, one-or one’s heirs-risks receiving the kind of letter Curator Stingone wrote me on April 23,2010.

* * *

Paul Brodeur was a staff writer at The New Yorker for nearly 40 years. His articles won many awards and fellowships-among them a National Magazine Award, an American Association for the Advancement of Science Award, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and an Alicia Patterson Foundation Fellowship-and resulted in his being elected to the United Nations Environ mental Program’s Honour Roll for outstanding envi ronmental Achievement. He is also a short story writer and novelist.