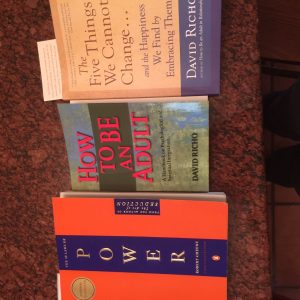

How to Be An Adult; Assholes: A theory; and Laws of Power

Three books: David Richo’s, Aaron James’, and Robert Greene’s.

I’ve been played by a few people over the last year and a half. One was someone with whom I’d had a peripheral acquaintance in grad school, who turned out to be a deranged psycho; one was a writer who wanted free editing and solicitous hand-holding so he could shop his novel to big publishers; and one was someone in the helping professions, who indulged himself at my expense. The last one should have known better.

After the fiasco with the writer–I spent Parvati Press funds on editing his manuscript–I woke up.

I realized that I have to be more careful. I have to be more discerning. Even if I intend to be a trustworthy person of integrity, I must accept that not everyone holds that same intention. There are people out there who just want to get what they can, and they don’t care how they do it or who they take advantage of in the process; people who indulge their own neediness and look for gratification without considering the impact on other people; and people who are just plain bat-crap crazy. Those latter folk can never be trusted.

Then there are people like me who do their best and still sometimes screw up, because everyone screws up, that’s human life. I need to know which group individuals belong to.

Given the vengefulness and malice my mother and former husband subjected me to over the years, I should have learned this lesson long, long, long ago. But that’s part of the problem with having the kind of early life I did, with unkind, untrustworthy parents. I have a giant blind spot when it comes to ferreting out the assholes.

So I did what I usually do, when confronted with a subject I want to learn: I turned to books. Hence the titles above.

Richo is a Jungian psychotherapist and prolific author. I own several of his books, including How to be an adult and The Five Things We Can Not Change. His work would have found its way into my hands sooner or later. He writes for people on the growth path, people who care about their evolution as human beings and who understand that psychological work necessarily carries a spiritual dimension. His work is about becoming a mature individual of integrity. It is about the practice of mindful loving-kindness as a way both to heal the past with its wounds and to identify your own transference. It is about the self-responsibility that leads to transformation and, ultimately, to waking up.

I’m glad I started with Richo. His work affirms my desire for, and intention toward, integrity, wholeness, and mindful loving-kindness. There’s a balance between Richo’s mindful higher self and the self-absorbed lower self of which James and Greene write; I now accept that I have to understand the lower self so that I can spot it when it acts out. Especially when it acts out in my direction.

James’ book Assholes: A Theory holds a neutrality I find fascinating. He describes a species of narcissist, examining their behavior, cultural origins, and impact with the same dispassion with which he’d treat a marsupial. It’s good, useful information–despite the title. I mean, I get why he uses that specific title, Assholes, despite how provocative that word is.

For anyone who has to deal with these entitled people, this book is worth reading.

Greene’s book The 48 Laws of Power is an outright appeal to the greedy, amoral, solely self-interested lower self, to the id, and basically to everything slimy within us that wants to control and manipulate other people. He’s saying boldly, “Here’s how to do it skillfully.”

I’m reading this book so I can suss it out when these tactics are being used on me. To be sure, I’m reading the book with as much disgust as interest. Greene foists some specious reasoning as to why it’s okay and even laudable to use his techniques, but it’s easy to see through the lame rhetoric of his justification.

In some ways, Greene has done me a service, by putting it down in black-and-white. His book will help me guard myself with more wisdom. Plenty of people use his tactics. Hopefully I can steer clear of them in the future. If I have to deal with those sorts, I will know their story. Forewarned is forearmed.

The contrast between Greene’s work and Richo’s work is shocking. Greene writes about power and greed and achieving the selfish ends of those; his work aggrandizes the ego. It goes toward materialism and consumerism–in healerspeak, the lower three chakras.

Richo’s work stands in startling contrast. It’s about the heart and spirit, integrating the shadow, opening the heart, and the personal responsibility and accountability inherent in spiritual and psychological integration.

The lower self vs. the higher self.

For example, Greene says, “Never put too much trust in friends” and Richo writes that everyone fails at times, so work on becoming a trustworthy person yourself. Greene writes, “Crush your enemy totally” and Richo writes “our psychological work…challenges us not to retaliate against those who have hurt us…The challenge is to meet our losses with lovingkindness.”

The question is, what kind of person do I want to be?

And even with a clear intention to be the absolute best Traci I can be, how do I achieve that intention?

Richo has an answer, I think. He suggests a few questions, when we’re facing troublesome situations with other people: 1, What in this is my own shadow? 2, What is my ego’s investment? and 3, How does this remind me of the past, that is, what is my transference?

So a shrink who holds sexual energy toward me is reflecting my own unacknowledged seductiveness. My ego wants to be special, to the shrink and to everyone. The transference is twofold: I try to please him by reciprocating his energy in order to elicit the “good daddy” I always longed for, and his refusal to validate me about the sexual energy he held toward me reflects my parents’ constant refusal to validate me ever about anything.

This experience disappointed me in myself. I should have known better. For one, every shrink I know socially is a complete nutter. For two, several of my friends grew alarmed at some of the shrink’s statements to me. One friend, a counseling MD with a degree in psychology, sat me down and explained how some of his comments contained hooks that were designed to lure me in. Another friend who is a PhD and a trained lay analyst looked at his texts and said, “Traci, this is seductive. Stop going to therapy.”

So why, with that kind of validation from my friends, did I still want this shrink to validate my experience, when he was clearly never going to own his own psychosexual countertransference?–Well, that’s the thing. Transference is a bitch. And it has us in its talons until we shake ourselves free.

This is just one example. It’s imperative that I see the tactics being used on me.

Richo insists that we must never give up hope in other people. He claims that everyone can have a change of heart and redeem themselves. And I like this aspect of his work, too, because even in bad experiences with other people, I’ve gained something positive and worthwhile. My mother gave me life. My ex-husband taught me about the person I don’t want to be and how essential respect is to me. The shrink helped enormously in several areas of my life. The arrogant writer showed me that I like helping other people on their journey to becoming authors.

The psycho, well, that’s harder to find the good. I wrote a Huffington Post article about it and received many warm accolades from people for sharing information on how to deal with harassment.

Gratitude is part of it, too.