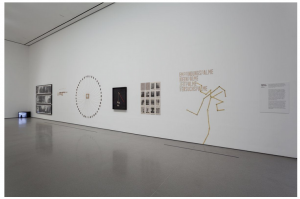

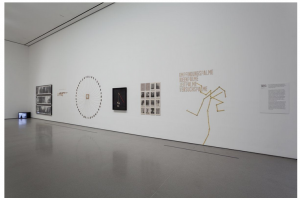

I saw a lot of art in Italy. The Accademia in Venice, the Uffizi in Florence, the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, the Canova Gipsoteca in Possagno, and a thousand Tintoretto/Tiepolo/Giovanni Bellini-graced churches in Venice. Then I came home to NYC and went to the MOMA with my museum buddy Ying.

The Exhibition Guide for the Sigmar Polke show was filled with the kind of pretentious art-speak that gives art historians a bad name because it distances viewers from art. For example, it describes Polke, a German artist who lived from 1941-2010, as having a “promiscuous intelligence.”

Ying and I had a conversation about that diction, “promiscuous intelligence.” Why couldn’t the writer just say Polke was interested in many subjects? Or something equally direct and to the point. It would be nice if artspeak didn’t try to call attention to itself, but rather served the art it references.

I should note that Ying is even more educated than I am, and has a few advanced degrees. She’s also one of the most dauntingly engaged readers I know. If she’s taking exception to word choice, her opinion matters.

My husband Sabin Howard the master sculptor has a lot to say about the vanity, self-importance, and general silliness of most art historians. He believes that great art should stand on its own, without need for the conceits and airs of PhD’s who are trying to justify their scholarly degrees.

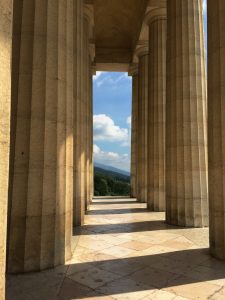

Indeed, no one needs to explain the immensity and gorgeousness of Giotto’s frescoes in the Scrovegni Chapel–they deliver themselves directly to your heart.

Sabin would have been skeptical of Polke, who worked in many mediums: painting, photography, film, sculpture, drawing, print-making, television, performance, and stained glass.

Sabin Howard is about mastery, uplift, perfection. Polke was about experimentation, curiosity, irreverence. Sabin operates from an admirable, even enviable, inner certainty. Polke was questing.

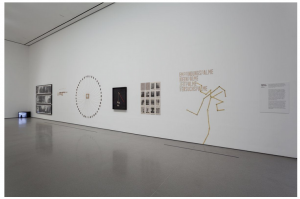

I enjoyed the show, though I did roll my eyes at Potato House, a wooden lattice with potatoes nailed into it that was supposed to evoke pedestrian objects in German life: the garden shed and the potato.

But I do like the wit and boundless curiosity with which the prolific Polke approached his art, and what do you call it if not art? In this I disagree with my husband, who would call it entertainment.

Maybe it isn’t the eternal high art of Michelangelo or Botticelli, but it’s valuable and important, partly as a cultural document–Polke grew up in post-war Germany, and that carries its own weight, a particular gravity. But Polke’s works offer more than cultural and historical reverence. His works attempt to change the viewer’s consciousness, to provoke questions and a kind of delicious uncertainty akin to Buddhist beginner’s mind. In that, it often succeeds.

Though I must agree with Ying who commented, “I like it, it’s very intellectual. But will I be thinking about it in two weeks? Will I be thinking about it in two hours?”

An insightful question, perhaps the salient question. I’m still thinking about Giotto’s frescoes and Botticelli’s Primavera.

Worth seeing, and do go to the Painting and Sculpture I floor, where are housed some stunning Kandinskys.